|

| The Beginnings Of The Texas Railroad System (Texas Academy of Science) |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Source: Source: Deussen, Alexander. “The Beginnings Of The Texas Railroad System”, Transactions Of The Texas Academy Of Science For 1906, Together With The Proceedings For The Same Year. Volume IX, p. 42-74. Austin, Texas: Published By The Academy, 1907. [Biography note: Alexander Deussen, M.S., was an instructor in geology and meteorology, University of Texas.] |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Jump to: |

|

| |

Section I. The Need Of Railroads.

Section II. Railroads Of The Republic Of Texas.

Section III. Progress Of Railroads In Texas, 1845-1856.

Section IV. State Aid To Railroads.

Section V. Railroad Regulation.

Section VI. Railroad Progress, 1856-1860.

Section VII. Conclusion.

End Notes.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

I. THE NEED OF RAILROADS. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Texas possesses very few natural facilities for transportation. Her rivers for the most part are un-navigable, and the soil of her black, waxy prairies renders wagon transportation in wet weather impossible. Isolated from her sister States, her most important need has ever been an adequate system of transportation—a system that not only makes possible communication between distant points within her own borders, but also affords an outlet for her products through St. Louis, Memphis and Chicago by land, and through Galveston and New Orleans by sea.

These considerations were apparent to the earliest settlers. It is, therefore, not surprising to learn that attempts were made as early as 1836 to secure such railroad system.

This paper purposes to give an account of the beginnings of this system. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

[top] |

|

| |

|

|

| |

II. RAILROADS OF THE REPUBLIC OF TEXAS. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

1. Texas Railroad, Navigation & Banking Company.

The Republic of Texas was but a few days old when its first railroad was chartered. This was in 1836, six years after the inauguration of the first steam railroad in this country. The charter created the Texas Railroad, Navigation & Banking Company, and authorized the corporation to connect the important Gulf ports of Texas with the rivers by canals, and to construct railroads whenever demanded by the public wants.[1] The corporators were Branch T. Archer and James Collingsworth—historic names in the annals of Texas.

These projects were never undertaken. The country was too much pre-occupied with civil conflicts; it had little time to engage in works of internal improvement. The rights granted were soon forfeited, and the Texas Railroad, Navigation & Banking Company passed into history. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

2. Other Railroads.

The Galveston & Brazos Railroad was chartered in 1838. W. S. Cooke, James F. Perry and others were authorized to construct turnpikes and railroads from Galveston Bay to Brazoria on the Brazos River, and to improve bays, rivers, bayous and creeks. This enterprise was intended to carry out on a more limited scale the plans of Archer and Collingsworth. Its ulterior object was to build up the city of Galveston by connecting this port with the fertile lands of the interior.

In 1839 a charter with similar powers was granted to parties in the interest of Houston to connect that city with Richmond, a town a few miles above Brazoria.

The Harrisburg Railroad & Trading Company was incorporated by parties in Galveston, and was given authority to connect Buffalo Bayou at Harrisburg, a point a few miles below Houston, with the Brazos River. The charter, although soon forfeited, suggested the later one, which found fruition in the completion of the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado Railroad.[2]

No work was done under any of these charters. The Republic of Texas lived and died without ever hearing the whistle of a locomotive. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

[top] |

|

| |

|

|

| |

III. PROGRESS OF RAILROADS IN TEXAS, 1845-1856. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

3. First Railroads of the State.

In 1846 two roads were chartered by the new State: The Lavaca, Guadalupe & San Saba, and the Colorado & Wilson Creek. These charters were soon forfeited.[1]

4. Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado Railroad.

In 1850 General Sydney Sherman, a veteran of the Texan War, organized the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado Railroad Company, to succeed the Harrisburg Railroad & Trading Company, which had become defunct. J. F. Barrett, of Massachusetts, was elected president, William Hilliard of the same State was elected secretary and treasurer, and J. S. Todd, of Texas, was elected resident director. This was the first successful attempt to enlist the aid of Northern capital in the development of Texas railroads. A charter was secured from the Legislature, and authority was given to connect Buffalo Bayou at Harrisburg, the supposed head of successful navigation, with the Brazos and Colorado Rivers. Galveston was in this manner to become the chief outlet for the cotton producing counties of the State.[2] Work commenced in 1851. By 1853 the road was completed twenty miles. In 1855 the line was opened to Richmond.

5. Galveston & Red River Railroad.

In 1848 Ebenezer Allen secured from the Legislature, in opposition to the wishes of the delegates from Houston, a charter for the Galveston & Red River Railroad. This charter authorized the construction of a railroad from Galveston Bay to the northern boundary of the State.

At the time of the passage of this act great consternation prevailed among the business men of Houston. Spurred on by the steady progress westward of the Galveston road, Houston negotiated with Allen for the commencement of the work at that city. Work was so begun in 1853,[3] and by 1855 the grading was completed to Cypress, twenty-five miles north of Houston.[4]

6. Mississippi & Pacific Railroad.

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 impressed upon the people of the United States the necessity of a trans-continental line to connect the shores of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. It was realized that such a road could only be constructed with the aid of the National government. In response to the popular agitation for the trans-continental railroad, Congress ordered a survey made of the several routes proposed, to ascertain which was the most feasible.

Texans were naturally very eager for the construction of the line that would pass through their State—that is, the Southern. In 1850 a resolution was passed by the Third Legislature, providing that aid should be extended to such a National railroad.[5]

[top]

The prospect that a company owning the franchise for the construction of the Texas link of the road would enjoy many excellent opportunities for speculation and profit called many corporations into existence, bent on securing this grant. During the year 1852 five companies were chartered and were given authority to construct railroads from the east boundary to the Rio Grande River. These were the Texas Western, the Texas & Louisiana, the New Orleans, Texas & Pacific, the Vicksburg & El Paso, and the Texas Central.[6]

The Texas Western and the Vicksburg & El Paso were afterwards consolidated. A substantial bonus—10,240 acres of land for every mile of completed road—was offered to each of these.

In 1853 Governor Bell urged the Fifth Legislature to extend a more liberal reward for the construction of the trans-continental road.7 Acting upon his suggestion, the Mississippi & Pacific Railroad was chartered. The act incorporating it directed the Governor to receive proposals from companies for its construction. The lowest bidder was to be granted the franchise. When complete, the railroad was to remain the property of the company for ninety-nine years. A large area of land was to be held in reserve for the company until the track was located. A new reserve was then to be created, extending thirty miles on each side of the right of way. After the construction of the first fifty miles, the corporation was to receive twenty alternate sections of land for every mile of completed road. A bond of $300,000 in gold was required to be deposited with the State Treasurer within sixty days after the signing of the contract, guaranteeing the construction of fifty miles within eighteen months.[8]

The Texas Western Company seeing here an opportunity to realize the purposes of its creation, had previously (during the pendency of the act) filed in the General Land Office a designation of its line along the proposed route of the Mississippi & Pacific.

The Atlantic & Pacific Railway Company was a corporation of New York, and Robert J. Walker, Secretary of the Treasury under President Polk, and at one time Governor of Kansas, and T. Butler King, formerly a member of Congress, were its directors and agents. This company determined to secure the sole franchise for the trans-continental road—not for the purpose of building it, however, but to gamble with its stocks and bonds. The first move was to buy up the charters already in existence, and to this end the Texas Western Company was paid $600,000 for its rights.[9] Thus were the purposes of the incorporation of the Texas Western accomplished.

[top]

When Governor Pease, who had succeeded Governor Bell, called for proposals to construct the road, only one bid was received. This was offered by the Atlantic & Pacific Company, and was accepted.

When it came to executing the contract, the resources and purposes of the Atlantic & Pacific Company were adequately ventilated. To meet the requirement of the deposit of the gold bond, the company offered stock of a Memphis bank. This being rejected by the Governor, the stock of the Sussex Iron Company of New Jersey was submitted. This was likewise refused. Seeing that these men were without means, the Governor annulled the contract.

Failing in their attempt to secure the franchise, they determined to prevent any other company from so doing. A reorganization was had under the Texas Western charter. This move effectually blocked any other company from offering proposals. When the Governor again called for them, none were received.[11]

When the Sixth Legislature convened in 1855, Governor Pease laid the matter before it. After a tedious debate an act was passed throwing the reservation open to settlement.[12] This in effect repealed the measure.

Subsequent events proved this to have been the proper course. The movement to build a Pacific railroad was premature. The country was too unsettled to attract private capital into such a stupendous undertaking. It was not until the National Government lent its aid that a trans-continental line was finally built. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

[top] |

|

| |

|

|

| |

IV. STATE AID TO RAILROADS. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

7. The First Subsidy.

To the railroads chartered by the Republic of Texas no encouragement was extended. The Texas Railroad, Navigation & Banking Company and the Galveston & Brazos Company were required to pay for their rights of way across the State, but to the Houston & Brazos Company and the Harrisburg Railroad & Trading Company this right was donated. To the first three railroads chartered by the State no aid was extended. However, their charters were more liberal than the preceding. None of these roads were built.

In the East many States undertook to further the construction of railroads by extending the aid of the commonwealth. New York voted to her railroads something like $8,000,000, $5,000,000 of which was granted to the Erie Railroad. In addition, $30,000,000 was granted by the cities and counties.[1]

Presumably patterning after this policy, Texas passed an act in 1850 permitting the cities and counties along the route to subscribe to the capital stock of the San Antonio Railroad. Under the terms of this measure, $100,000 was subscribed by the city of San Antonio and the county of Bexar, making the first substantial bonus offered to a railroad in Texas.[2]

8. Land Grants.

In 1850 Congress granted to Illinois 2,500,000 acres of public domain, to be applied to the construction of the Illinois Central Railroad. By this means, this road was soon completed.

Texas followed the example of Illinois. She had an immense public domain of her own. In this respect she was unique in the sisterhood of States.[3] It is estimated that upon her entrance into the Union, she had 181,965,832 acres of unappropriated land.[4]

[top]

Realizing the necessity of aiding the private companies, she donated to the Henderson & Burkville Company in 1852, 5,120 acres of land for every mile of road it constructed. Similar donations were made to fifteen of the twenty-three railroads chartered between this date and January 1, 1856.[6] To the San Antonio Railroad, the La Salle & El Paso, the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado, and the Galveston & Red River, all of which were chartered prior to 1852, 5,120 acres were also granted by subsequent acts.[7]

It was soon evident that these subsidies would not be sufficient. In view of this fact, the law of 1854 was passed granting 10,240 acres in alternate sections to the mile to every railroad that should construct twenty-five miles of road within the two succeeding years.

9. Causes of the Failure.

These measures did little to relieve the situation. Of the thirty-seven railroads chartered before 1856, twenty were entitled to receive land from the State. Of these twenty, only two were built by 1856. Of the 18,374 miles of railway in operation in the United States at that time, only forty were in operation in Texas.

This disappointing condition of affairs was almost entirely due to the scant settlement. In 1860 the population did not exceed 604,215, or 2.3 to the mile. The metropolis numbered 8,235 people.

Only five cities had over 2,500 inhabitants. One hundred and twelve of the 243 counties of Texas today contained not a single settler.[8]

[top]

It will be seen that the business in this State was not sufficient to make railroads paying investments. With opportunities for profit so remote, it was idle to expect capital to be invested in these enterprises.

The limited aid extended by the State thus far was accompanied with one result. The franchises were secured by men without means, who intended to use them not to build railroads, but to speculate with them. These charters were either disposed of to other speculators at a premium, or were used to defraud the people of their money.[9]

Assuming that the promoters were honest in their intentions to build the roads, it is evident that their only available resource was the capital the citizens of Texas could be induced to subscribe, and this was insufficient.

In 1858 the free capital was estimated at $2,745,493.[10] Its extreme paucity is further illustrated by the following incident, which is typical: When the Buffalo, Brazos & Colorado road proposed to extend its line from Richmond to Austin, a subscription was taken by the company from the citizens of Colorado, Fayette, Bastrop and Wharton counties. Only $54,025 was subscribed, and not all of this was collected. This was hardly sufficient to pay for five miles of road.[11] Yet the citizens of these counties were exceedingly anxious for railroad connection with the Gulf, and the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado road was one that commanded more confidence than any other company in Texas.[12]

It is evident that any aid extended by the State short of the amount necessary to construct the roads must be accompanied by inevitable failure. If the roads were to be built, more aid was an absolute necessity.

[top]

10. Agitation for State Ownership.

(a) Public Works in Other States.

When the utility of railroads was first fully appreciated, many schemes of internal improvement were set on foot in the United States. Into private enterprises capital could not be lured; but into public enterprises it readily found its way. Internal improvements were possible only at first by using the machinery of the State.[13]

It was in this manner that many of the earlier improvements in the United States were constructed. Thus, the Erie canal was built in New York in the early 20 's.[14] The first railroads of Pennsylvania were likewise built at a cost of over $40,000,000. Indiana and Illinois expended $15,000,000 each on similar projects. Michigan undertook State works at first. In Georgia, the Western Railroad, 130 miles in length, cost the people $5,000,000.[15] It was not until the profitableness of works of internal improvement was demonstrated in these States, that private capital sought them.

(b) Earlier Proposals for a State System.

There had been since the earliest times a faction in Texas that had contended for public works. In 1842 a railroad convention was held at Houston, and recommended the adoption of the State system.[16]

In 1850 John W. Dancy, who afterwards represented Payette, Bastrop and Travis Counties in the Sixth Legislature, proposed the following plan: By means of the public domain and $5,000,000 then in the treasury, the State was to construct trunk roads running from Galveston and Matagorda Bays, and intersecting roads running east and west. This system would give direct connection with New Orleans, Vicksburg and Memphis. Slaves were to be used on these roads, and a permanent advantage would thus be gained, thought Mr. Dancy, in opening a new field for slave labor in the South.[17]

[top]

The advocates of public works, at first few, increased in numbers as the true state of affairs became apparent.[18] The futility of the attempts to attract private capital was beginning to be appreciated. The failure of the corporations gave force to the arguments. The Mississippi & Pacific fiasco in 1855 drove the lesson home. Says Governor Pease:

"The active capital in the hands of our citizens is insufficient to insure their (railroad) construction. * * * It can not be disguised that the population and business of the State are not such at this time as to promise the return of an immediate profit on the amount that may be invested in such enterprises." [19]

The men who espoused the cause of public works contended that no transportation system could be secured at any time within the near future unless the example of the East was followed, and the machinery of the State was used.

In 1855 and 1856 the agitation for internal improvements became especially violent. Railroads were the chief issue in the gubernatorial election of 1855. More liberal legislation was urged by the public press and public men. Conventions were held in many counties, and recommended liberal aid. In many communities it was warmly urged that the State plan be adopted. [20]

[top]

(c) Governor Pease's Plan.

Governor Pease was one among the number who came to believe that the capital necessary for the works could best be secured by using the credit of the State. In his message to the Sixth Legislature in 1855 he elaborated a scheme for internal improvements, and recommended its adoption by the State. The essence of this plan was as follows:

A general system of internal improvements, consisting of railroads, river improvements and canals, was to be built by the State with the aid of the public domain. Thirty million dollars of bonds were to be sold, the proceeds of which were to furnish the means for the immediate construction of the works. The interest on the bonds was to be defrayed by the levy of a small internal improvement tax, and the principal was to be redeemed from the proceeds of the sale of the public lands. In order to make the system permanent and to insure its successful completion all of its features—even the particular works to be undertaken—were to be incorporated in the Constitution.[21]

11. The Loaning System, (a) History of the Loan Bill.

There were a great many men in Texas, on the other hand, who were bitterly opposed to State works, on the grounds of their costliness. While conceding the necessity for railroads, these men believed that the capital necessary for their construction could best be secured by the adoption of a more liberal policy on the part of the State toward the corporations then in existence.

When Texas was admitted to the Union, she claimed in addition to her present domain all of the territory of New Mexico east of the Rio Grande River and south of the present northern boundary of the State. During the Mexican War General Kearney took possession of this country. The North was opposed to relinquishing this area back to Texas, for fear of extending the slave territory. In satisfaction of her claims to this region, Texas received from the National government $5,000,000.[22] By Act of January 31, 1854, $2,000,000 of this $5,000,000 was set aside for the public schools and designated the Special School Fund. [23]

[top]

It was at once suggested that these funds should be applied to the construction of internal improvements. Governor Bell made such a recommendation in 1851, but it was not acted upon at this time. In 1853 Governor Pease recommended the establishment of a board of commissioners to make loans from these funds to the railroads, to

aid in their construction.[24] This measure was defeated by the men who favored public ownership.

When the agitation for railroads became violent in 1855, such a measure was again introduced in the Legislature in opposition to the plan of Governor Pease, who had by this time embraced the policy of State ownership, and recommended its adoption by the State. After a tedious debate extending over the greater part of the session, this act was passed over the opposition of those men who favored public works. The agitation for government ownership thus came to naught.

(b) Terms of the Act.

According to the terms of the act, all the railroads then in existence were to be loaned $6,000 for each mile of road constructed, after the completion of the first twenty-five miles, and the grading of the second twenty-five miles. The Special School Fund, consisting of $2,000,000, was to be equally divided between the roads on the east and west sides of the Trinity River. The loans were to be made by a Board of School Commissioners, consisting of the Governor, the Comptroller and the Attorney General.[25]

12. Resume.

The method of securing railroads adopted by Texas was, therefore, the system of private corporations aided by the State. The aid offered consisted of 10,240 acres of land and a loan of $6,000 to the mile of road constructed. How efficient these measures were in promoting construction we shall learn in another chapter. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

[top] |

|

| |

|

|

| |

V. RAILROAD REGULATION. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

13. Railroad Abuses.

Though the agitation for public works and the abolition of private corporations failed, it was at least accompanied with some important results. The first attempts at railroad regulation, and the correction of railroad abuses came as a result of this agitation, and it cannot be said that the cause of railroads was not benefited thereby. The abuses to which reference is had were not unlike some that prevail today—abuses which the experience and legislation of three-quarters of a century is apparently powerless to check. A fair sample of some of these is the following:

When the Mississippi & Pacific contract was signed, it was agreed between the contractors and the Atlantic & Pacific Company that they were to be paid $200,000—to be later increased to $600,000—in Atlantic & Pacific stock. It was claimed by Mr. Lawhon that $20,000,000 of stock would have to be issued under this arrangement in order to net the $600,000, and upon this fictitious value the people were to pay dividends in the form of exorbitant tariff and passenger rates.[1]

The Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado Company was guilty of similar manipulations. After expending the money paid in the form of stock, the company resorted to borrowing. Ten per cent bonds were issued, $66,000 of which were sold at thirty to sixty cents on the dollar. The road when completed to the Colorado cost $1,040,793.[2] One-half the sum nominally expended should have been sufficient to complete the work. In order to make dividends on the stock, and to pay interest on the bonds, rates had to be levied two or three times higher than they normally should have been. [3]

[top]

The San Antonio & Mexican Gulf Railroad solicited subscriptions to its capital stock on an estimated cost of $14,000 to the mile. The contract was let at a cost of $27,000 to the mile. This exorbitant cost was due to the fact that the contractors agreed to take the bonds of the company in payment. The difference of $13,000 represented the discount at which the bonds had to be negotiated. Here again the people paid the difference. The produce of the country had to be taxed sufficient to pay the interest and principal on bonds which represented largely a fictitious value. [4]

14. Governor Bell's Administration.

The pernicious character of these abuses was recognized as early as 1853, for in that year Governor Bell writes in his message to the Legislature:

"Already some twenty or more charters have been granted by the State government for railroad purposes, and so far as I am advised, with few exceptions, * * * they have been unattended with the practical results anticipated, notwithstanding the liberal inducements offered. * * * Consideration of these facts has convinced me that in our zeal for internal improvements we have heretofore granted railroad charters indiscriminately. * * *

"I therefore recommend that no railroad shall be incorporated, except such as are clearly of primary importance to an extensive section of the State, and which would give the safest guarantee of its ability to comply with the terms of its charter.'' [5]

These recommendations were incorporated into a law in 1853—the first general law passed by Texas seeking to regulate railroads. This act contained the germs of all the future legislation on the subject of railroad regulation. Annual reports were required of the companies, giving detailed information as regards the operations of the roads. The Legislature reserved the right to fix a schedule of freight and passenger charges once in every ten years. No reduction of rates was to be made, however, unless the net profits for the preceding ten years had exceeded twelve per cent on the investment. Another provision having in view the absolute control of the companies, gave authority to the Legislature to acquire any railroad property at any time by paying the cost of the road, plus twelve per cent.

[top]

15. Governor Pease's Administration.

Governor Pease did not consider these measures comprehensive enough. He wished to make it impossible for companies to secure charters for speculative purposes, and he desired to protect the honest citizen and the State from imposition and loss. In his first message to the Fifth Legislature he recommended a course of action in regard to charters already granted, as follows:

"I * * * recommend that no extension of time shall be granted to any company unless satisfactory evidence is presented that it has actually commenced the construction of its road and that a sufficient amount of stock has been paid to * * * (insure) that the road will be completed. * * * The route and termination of the road * * * (should) be designated when this has not been done in the original charter, and if any further donations of land are made to such companies they should receive the patents only on the final completion of their road." [6]

No action was taken on these recommendations. However, in amendments to the charters of the San Antonio & Mexican Gulf and the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado Railroads the privilege of building branches was rescinded. [7] Governor Pease in his message to the Sixth Legislature, advocating the State system, reiterated the recommendations of his first message, and urged the adoption of the necessary regulations in case the corporate system was continued. He failed in his attempt to establish the system of public works, but he determined to engraft these regulations in the charters of the companies. In this purpose he was successful.[8]

In December, 1855, the Galveston, Houston & Henderson Company applied to the Legislature for an extension of time. When the bill came up in the House an amendment was offered, reserving the right for the State to buy in this road at any time by paying to the company an amount equivalent to the value of the road plus ten per cent. It was held by the supporters of this amendment that the provision in the general law requiring the cost of the road to be paid to the company, instead of its value, destroyed the possibility of exercising control, since the road would be unprofitable to buy. They insisted, therefore, on its alteration. The relief was extended to this company, but no such right on the part of the State was asserted.[9] The company was required to keep its principal office in the State, to hold all elections, and to have a majority of the directors reside in Texas.[10] Similar terms were imposed on the Galveston & Red River Company and the Memphis, El Paso & Pacific Company when they applied for relief. Branching privileges were denied all three.

[top]

A bill granting relief to the Texas Western Railroad passed the Legislature at this time, but was vetoed by the Governor because it did not impose these conditions. This corporation was powerful enough to lobby this measure through at the adjourned session over the Governor's veto, and this company escaped without the onus of these restrictions. Branching privileges were denied, however. [12] The Henderson & Burkville Company likewise secured relief in spite of the Governor's veto. [13]

Six new companies were chartered by the Legislature during the year 1856, and the charters of all of these, with the exception of the Houston Tap road, contained these provisions. The Trinity Valley charter was vetoed by the Governor because it did not impose the new regulations. The franchise was not granted until 1860, by which time the observance of these conditions had become compulsory by general law.[14] The Jefferson & Dangerfield charter experienced similar vicissitudes, but never became a law.

In his retiring message to the Seventh Legislature, Governor Pease again deprecated the prevalence of loose methods in railway legislation, and urged the necessity of uniformity in granting charters. [15]

The people of the State had by this time become convinced of the soundness of his views, and showed less disposition to distrust his motives. Their representatives responded to the suggestions, and inaugurated uniformity by the passage of a general law. This was a supplementary act to the general regulating act of, 1853. The termini of the routes were required to be designated, the principal office was required to be kept along the road, and the chief officers and directors were required to reside in Texas. [16]

The importance of these enactments, though little understood at that time, is thoroughly appreciated at this day. These laws doubtless protected the State from many evils from which it stood in need of protection. Though often violated in after years, they still exerted a wholesome influence on the railroad development. In them we must seek for the beginnings of our Railroad Commission and our salutary Stock and Bond law. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

[top] |

|

| |

|

|

| |

VI. RAILROAD PROGRESS, 1856-1860. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

16. Introductory.

The progress of railroads in Texas has been traced down to 1856. Only two lines had then been constructed, aggregating forty miles. These were the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado, and the Galveston & Red River Railroads. I purpose now to indicate the progress of railroads down to 1860, or the beginning of the Civil War.

17. Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado Railroad.

By 1856 the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado Railroad had reached Richmond on the Brazos, a distance of thirty-two miles from its starting point. While the earnings of this section were much greater than those of the short section of twenty miles, still these were insufficient to make the road profitable. The country along the Colorado valley, on which its future mainly depended, would not continue to seek an outlet by it, unless it was quickly extended to this river.

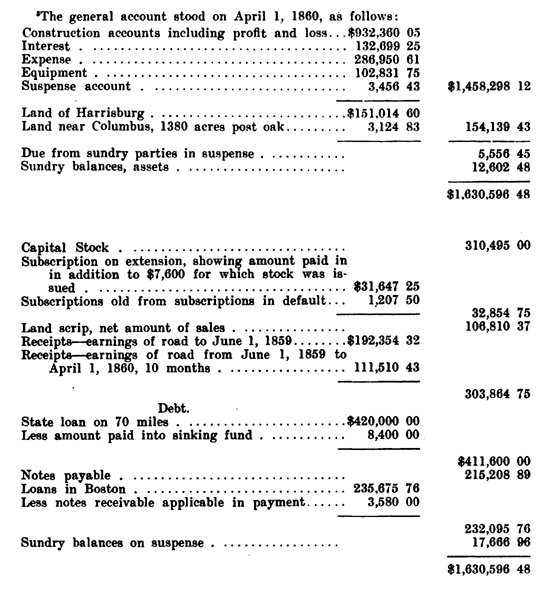

The passage of the Loan Act in 1856 induced the company to undertake this extension. The route was surveyed and located to a point near Columbus on the Colorado River, forty-eight miles from Richmond. By December 8, 1857, twenty-seven miles had been graded under contract with Cooper & Company. Work under this contract then ceased on account of a lack of funds. A new contract was entered into with H. K. White & Company, and the work was resumed on the 1st of June of the following year. The road was completed and opened for business to East Bernard, fifty miles from Harrisburg, about April 1, 1859, and to Eagle Lake, sixty-eight miles from the starting point, by October 6, 1859. Seventy miles were completed soon after. Work on the road to the point near Columbus, eighty and one^half miles from Harrisburg, was in progress in 1860. The grading was completed, and the seventy-fifth mile finished on May 23rd. The inception of hostilities put a stop to further progress.

[top]

These seventy-five miles of road, completed before the Civil War, were built by the following means:

The amount realized from the issuance of capital stock was $311,702. The citizens of Colorado, Fayette, Bastrop, Travis and Wharton Counties donated $24,047.25. 718,080 acres of land were received from the State under the various land donation acts. Of these, 141,160 had been located and patented. 588,800 acres were disposed of, netting to the company $106,810.37, or about five and a half cents an acre.

The loans received from the school fund, under the terms of the acts of 1856 and 1858 amounted to $420,000.[1] $232,095.76 was secured from parties in Boston for which bonds were issued. In addition $215,208.89 was received by the company in the form of supplies, equipment, etc., for the payment of which notes were given.[2]

These amounts aggregated $1,209,846.27.[3]

18. Houston & Texas Central Railroad.

The beginnings of the Galveston & Red River Railroad have already been described. Nothing much was accomplished during the year 1853 owing to the sore financial straits of the company.

In 1855 a contract was closed for the construction of twenty-five miles of road. After many delays, and after the granting of an extension of time by the Legislature, this section was completed in 1856, and trains were then run to Cypress City daily.

With the permission of the Legislature, the company assumed the name of the Houston & Texas Central Railway Company.

[top]

In order to receive a loan from the school fund a contract was let for the completion of the second section. This was finished to Hempstead, a distance of fifty miles from Houston, in January, 1858. During the year 1859 work on the road progressed steadily. By October 1st of that year, seventy-five miles were in operation. In 1860 the line was completed to Millican, eighty miles from Houston. Construction was then suspended on account of the war.

This company had great difficulty in securing funds with which to prosecute construction. In 1854 Paul Bremond, who had succeeded

Ebenezer Allen to the presidency, visited the Eastern States and Europe for the purpose of securing capital to carry on the enterprise. In this mission he was unsuccessful. After the first section of the road was built, some northern capitalists were induced to buy stock.

The amount realized by the company on the sale of stock was $778,675.00.[5] 512,000 acres of land were received from the State, but up to June 1, 1860, no money had been realized from its sale. $450,000 was received in the shape of loans from the school fund. In addition to the above the company owed $125,000 in the form of seven per cent, bonds, which had been created in favor of J. H. Wells & Company to replace an original mortgage of $1,000,000; and in the form of bills payable, $224,430.[6]

These sums aggregated $1,578,105.[7]

[top]

19. Galveston, Houston & Henderson Railroad.

The Galveston, Houston & Henderson Railway was chartered in 1853 to connect the cities designated in its name.[8] It was begun at Virginia Point, on the northern shore of Galveston Bay on March 1, 1854. The first section of twenty-five miles was completed in 1858. The charter required the construction of forty miles by the 1st of November of this year. This the company failed to do, and the franchise was in consequence forfeited. It was revived by the Legislature on the condition that the forty miles be finished by the 1st of November, 1859. The terms of this condition were complied with. In this same year a bridge was built over Galveston Bay by the city of Galveston, and donated to the company. A junction was effected with the Houston & Texas Central at Houston, and the line was opened between Galveston and Houston in 1860.

The only aid received by this company was the bridge across Galveston Bay. The city of Galveston issued bonds with which to construct this bridge, and permitted the company to use it. The corporation agreed to pay the interest on the bonds as it became due, and the principal at maturity. When these obligations were discharged, the bridge became the property of the company.

The amount received in the form of subscriptions to capital stock was $32,363.29. The indebtedness of the company at the time of the opening of the line was $387,969.24.[9]

[top]

20. San Antonio & Mexican Gulf Railroad.

The San Antonio & Mexican Gulf Railroad Company was chartered in 1850 to connect San Antonio with the Gulf.[10] In the spring of the year 1852 a survey of the road was made, and in 1853 it was put under contract. But the company lacking financial means was unable to make any progress. For two or three years it held out proposals to the little towns along the coast offering to start the road at the town making the largest donation. Inspired by the hope of a loan from the school fund, the company was reorganized in 1856, and a new charter was secured from the Legislature.[11]

A new contract was let for the building of the forty-five miles of road between Powder Horn and Victoria with a branch to Lavaca. Operations were soon suspended, however, on account of a lack of funds. In 1859 the road was sold to meet the liabilities incurred for iron and material used in construction. A new company was now organized to build a road between Lavaca and Victoria, the plan of extending to San Antonio being abandoned. By 1860 the road was graded between Lavaca and Victoria, and five and a half miles were put in running order.

This company had great difficulty in securing funds with which to carry on its work, as will be apparent from the foregoing recital. Two or three attempts were made to enlist the services of foreign capital, but these proved unsuccessful.

$320,000 was subscribed in the form of capital stock, $100,000 of which was subscribed by the city of San Antonio and Bexar County. It is interesting to note in this connection, however, that San Antonio never received any benefit from this subsidy, because the road never reached there. $47,470.00 of this capital stock was paid in the form of land. 64,000 acres of land were received from the State, but no money thus far been realized from sales.

The total available resources of the company, therefore, which had furnished the means of completing the five and a half miles of road was its capital stock of $320,000.[12]

[top]

21. Houston Tap Railroad.

While the Legislature had under consideration the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado charter, the representatives from Houston would not give their support to the measure until an amendment had been inserted giving to Houston the privilege of tapping the road.[13] The steady progress westward of the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado Company induced Houston to make an attempt to compete for the trade of the Colorado country by offering railroad connection with this city.

A charter for a tap road was secured by the corporation of Houston in 1856.[14] The city was authorized to levy a tax of one per cent, by consent of a majority of its voters. Bonds were authorized to be sold, the proceeds of which were to be used to construct the road. Under this authority the tax was voted almost unanimously, and the road was built during the year 1856.[15] It was sold to the Houston Tap & Brazoria Company in 1859 for $172,000, $130,000 of which was paid in the stock of the purchasing company, and $42,000 of which was paid in cash out of the loan from the State.[16]

[top]

22. Southern Pacific Railroad.

The early history of the Texas Western Railroad has already been touched upon in connection with the Mississippi & Pacific road. It was there stated that the sale of the charter was forced upon the Atlantic & Pacific Company by virtue of the Texas Western Company's preemption of the most available route. Failing to carry out its contract with the State, the Atlantic & Pacific Company reorganized under the Texas Western charter at Montgomery, Alabama, in 1854, and used this franchise in preventing any other corporation from building the Mississippi & Pacific road.

In 1856 the charter was amended, and the name of the company was changed to the Southern Pacific.[17] In this year work was begun on a branch line to Caddo Lake north of Marshall. Over this branch the track material for the main line was brought. By February 10, 1858, twenty miles were completed. Seven and one-half miles were added during the following year, and this marked the extent of the work done before the Civil War.

This company led a checkered existence. A few statements depicting its financial history will explain the slow progress made in railroad construction in Texas before the Civil War.

It issued over $14,000,000 in stock. The following were some of the purposes for which these enormous fictitious values were created:

The Sussex Iron Company of New Jersey was bought for $6,000,000 of the Texas Western stock, worth about $300,000. The Texas Western Company also transferred to Dr. Jeptha Fowlkes $8,000,000 of stock for bonds payable in one, two, three, four and five years, and secured by mortgages on swamp lands in Arkansas at the rate of five dollars an acre. Mr. Edwin Post entered into a contract with the Executive Committee by which he was permitted to subscribe for $2,000,000 of stock at any time. In April, 1857, the limit of stock sales was fixed at $12,000,000, although some $14,000,000 had already been issued. Mr. Post was paid 13,333 shares, worth about $66,666.66 to cancel his contract. Many other transactions on a smaller scale might be enumerated to illustrate this pernicious practice of issuing stock without obtaining anything of value in payment of it.

[top]

The amount of money actually expended in Texas did not exceed over $391,925.98. This seems to have been derived from the following sources:

The amount collected from stock sales did not exceed $27,000. The following record of loans is available:

King, Todd & Archer --- $ 4,000.00

R. J. Walker -- 500.00

Stillman, Allen & Co., about --- 20,000.00

Parties in Marshall --- 10,000.00

Total $34,500.00

The balance of the amount expended seems to have been derived from donations by the citizens of Texas.

By 1858 the company had become so burdened with debt, that it was sold out by the creditors under a deed of trust.[18] It was purchased for $40,000 in cash by Dr. Sanders of Marshall, and was in turn sold by him to the creditors. These parties effected a reorganization. They were soon involved in a controversy with the members of the old company who claimed that the sale was illegal.[19] Suit was brought by them against the new organization. At this juncture the State filed a suit for a forfeiture of charter because of the failure of the company to remove its general office to Texas and to file its annual report with the Comptroller.[20]

In September, 1860, another sale of the company took place. This sale freed it from encumbrances. All the difficulties were adjusted, and the original stockholders were again taken back into the company. The State suit against it was dismissed, and the troubles of the Southern Pacific Company were over for the time being.[21]

[top]

23. Memphis, El Paso & Pacific Railroad.

Another of the companies called into existence by the agitation for a southern trans-continental line was the Memphis, El Paso & Pacific, chartered in 1853.[22] It was the intention of this company to unite with the Texas Western at some point in the interior. While the Texas Western road would thus afford connection with the Mississippi at Vicksburg and New Orleans, the Memphis, El Paso & Pacific would afford connection with the Mississippi at Memphis and Cairo.

The efforts to secure funds at this time proved unsuccessful, and after a number of extensions of time had been granted, the charter was finally forfeited.

In 1856 a new charter was secured. Eight miles of public land on each side of the right of way was reserved in which the company could locate the sections of land it was entitled to under the act of 1854. This was the most liberal charter thus far granted by the State of Texas.

Work was begun in 1857 near Texarkana. Forty-seven miles were graded and made ready for the reception of iron. Engines and cars were purchased and delivered to the company by Red River steamers landing at Moore's Ferry on Sulphur Fork. A great overflow in Red River occurring about this time, added over a mile of timber to the raft then existing, and prevented further delivery of material. A branch road was therefore undertaken from Moore's landing to Jefferson, which would remove this difficulty. Five miles of this branch were completed before the War.[28]

The amount of money received from the sale of stock was $70,707.09. The only aid received from the State was certificates for 262,400 acres of land. 191,680 of these were alienated by 1861. In this connection it is interesting to note that the president's salary, amounting to $3000 a year, was paid in land certificates from May 9, 1856, to May 9, I860.[24]

[top]

24. Washington County Railroad.

When a relief bill for the Galveston & Red River Railroad came before the Legislature in 1856, the branching privileges were restricted until the road reached Red River. This was fatal to the hopes of the citizens of Washington County, who had subscribed stock in the expectation that this company would build a branch from its main line through Washington County to Austin.[25]

Nothing daunted by this awkward legislative enactment, the planters of Washington County, who had amassed considerable wealth, determined to build a road of their own to connect their city of Brenham with Galveston direct.

A charter was applied for, and was secured on February 2, 1856. This charter created the Washington County Railroad. Work was commenced in July, 1857, at Hempstead on the Houston & Texas Central Railroad, and completed to Chappell Hill, a distance of eleven and a half miles, on May 1, 1859. The road progressed steadily during the succeeding years, and so fixed was the determination of these people that the section to Brenham was completed after the breaking out of hostilities.

The capital stock subscribed was $270,000, of which $160,000 was paid in. All of this was bought by the citizens of Washington County. The Loan Act authorized loans to be made only to the companies chartered previous to its passage. This excluded of course the road under consideration. By special act it was authorized to receive a loan.[26] Under this authority $66,000 was received. 112,640 acres of land were received, 100,000 of which were located in Harris, Liberty and adjoining counties. 12,160 of these acres were sold during the year 1860.[27] The indebtedness in 1860 was $160,000.

[top]

25. Houston Tap & Brazoria Railroad.

The Houston Tap & Brazoria Railroad was chartered in 1856 for the purpose of extending the Houston Tap road to Columbia on the Brazos River, thus opening up the great sugar producing section of the State. The grading was finished to Columbia in 1859, and the road was completed to that place in 1861. The city of Houston transferred to the company the Houston Tap road, as remarked in a previous place. Work on the western division between Columbia and Wharton was in progress in 1860 and 1861, but the outbreak of the war prevented its completion.[28]

The amount of capital stock subscribed was $380,000, nearly all of which was paid. This was almost entirely subscribed by the planters along the route. The county of Brazoria by authority of the Legislature donated to the company $100,000 in bonds. The company was extended permission to receive loans from the school fund,[20] and it received aid from this source to the extent of $300,000.[30] In addition it received from the State 64,000 acres of land, 35,840 of which were disposed of during the year 1860, yielding to the company $11,350.00. The indebtedness in 1860 was $411,560.01.[31] These sums aggregated $1,202,910.01. The cost of the road was about $10,000 a mile.

[top]

26. Texas & New Orleans Railroad.

New Orleans desired to compete with Memphis, Chicago and St. Louis for the trade of Texas. To accomplish this, the Texas & New Orleans Railroad between New Orleans and Houston was projected. This road was chartered under the name of the Sabine & Galveston Day Railroad & Lumber Company on September 1, 1856.[32] At the same time a charter was granted by the State of Louisiana to the New Orleans & Opelousas Railroad to connect Berwicks Bay with the eastern terminus of the Sabine & Galveston Bay road at Orange.

Work was begun in the spring of 1858. During this year the line was partially graded between Houston and Liberty. In 1859 the name of the company was changed to the Texas & New Orleans.[33] By the 1st of August, 1860, the road was completed between Orange and Liberty, a distance of sixty-six miles.

During the year 1860 four loans were received from the school fund aggregating $430,500.[34] The cost of the road was about $30,000 a mile.

[top]

27. Indianola Railroad.

The spirit of rivalry for the trade of the interior which made Houston and Galveston such bitter enemies, had its counterpart in the enmity between Lavaca and Indianola. When the San Antonio & Mexican Gulf Railroad was chartered with its terminus at Port Lavaca, the citizens of Indianola undertook the construction of the Indianola Railroad. The company was chartered in 1858, to construct a road from Powder Horn Bayou to Austin. By act of 1860 the company was required to connect with the San Antonio & Mexican Gulf road within a year, and was authorized to sell to this company the roadbed then graded. The war put a stop to further operations.

The report of the Indianola Railroad to the Comptroller for' the year 1860, showed $28,485 paid on its capital stock.

[top]

28. Mexican Gulf & Henderson Railroad.

In 1852 the Henderson & Burkville Railroad was chartered to connect Henderson in Rusk County with Burkville in Newton County.[36] This charter was amended in 1854 so as to allow the company to begin on the coast.[37] In 1856 its name was changed to the Mexican Gulf & Henderson Railroad.[38]

Work was begun in the spring of 1857 at Pine Island Bayou, eight miles north of Beaumont. The timber was cleared away and the roadbed grubbed for several miles. These operations were soon suspended. When the Eastern Texas Railroad was chartered it was required to pay $3000 to Ferguson, Alexander & Company for the work that had been done—a sad but typical commentary on the financial ability of these pioneer railway companies.

[top]

29. Eastern Texas Railroad.

The Mexican Gulf & Henderson Company was succeeded by the Eastern Texas Company. This road was chartered in 1858 to run from Sabine Pass to the northern counties of the State.[39] Fifty thousand dollars was required to be deposited by the company with the State Treasurer before any rights vested under the charter.

This sum was to be returned when twenty-five miles of the road were completed.

Grading was commenced some fifteen or twenty miles south of Beaumont with the purpose of making Sabine Pass the terminus. The road between these two places was completed in 1861. The $50,000 deposit was never made.

[top]

30. Aransas Railway.

The Aransas Railroad was another fiasco of the times. The company was chartered in 1852 for the purpose of constructing turnpikes from Aransas Bay to Goliad.[40] In 1858 it was changed from a turnpike to a railroad company.[41]

The idea was soon conceived of turning this pigmy road into a trans-continental line. The company allied itself with a corporation organized in Washington City, and acting under a franchise from the Supreme Government of Mexico, the Washington company purposed to extend the Aransas road through Mexico to the Pacific Ocean. This constituted the so-called Central Transit Railroad.

How much of this magnificent scheme was realized? In 1858 a roadbed was opened across Live Oak peninsula near Aransas. In 1859 the grading across the shallow water separating the main land from deep water of Aransas Bay was completed; and these six or seven miles of embankment was all that ever materialized of the great Central Transit Railroad. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

[top] |

|

| |

|

|

| |

VII. CONCLUSION. |

|

| |

This completes the account of Texas railroads before the Civil War. Fifty-one companies were chartered, but only fourteen roads were built. During a period of twenty-four years 284 miles of railway were constructed out of a total of 30,626 in the United States.

This survey should make clear the causes that occasioned these mediocre results. The lesson to be drawn from the narrative is the folly of the attempt to build railroads before a country is ready for them. Capital will not seek them until they are profitable. Limited State aid but serves to attract speculators. A few scattered miles of railroad are built, but the great percentage of chartered mileage is not. The people are defrauded of their scant wealth, and exorbitant issues of stocks and bonds eat up the profits of their produce. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

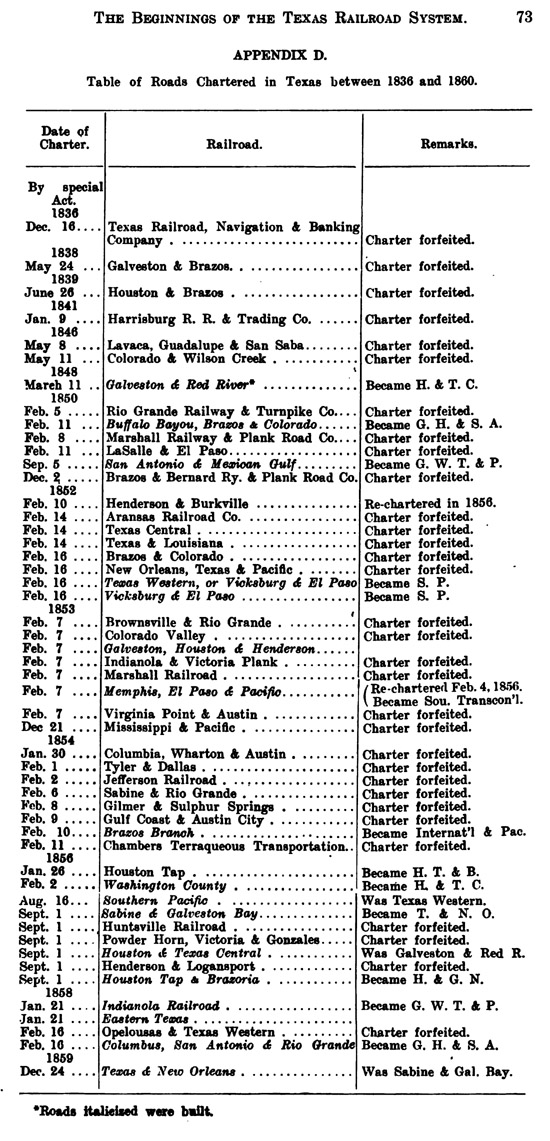

APPENDIX C. |

|

| |

The following table shows the miles of railway in operation in Texas at the end of each year, and the annual increase down to the Civil War.

End of the Year, Miles in Operation:

1854: 32

1855: 40 (increase of 8)

1856: 71 (increase of 31)

1857: 157 (increase of 86)

1858: 205 (increase of 48)

1859: 284 (increase of 79)

1860: 307 (increase of 23) |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

[top] |

|

| |

|

|

| |

NOTES. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

NOTES FOR SECTION II., RAILROADS OF THE REPUBLIC OF TEXAS.

[1] -- Act of December 16, 1836, Gammel's "Laws of Texas," Vol. 1, p. 1188.

[2] --The facts of this account are taken from an article by Donaldson in the Texas Almanac for 1868, pp. 119-121. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

NOTES FOR SECTION III., PROGRESS OF RAILROADS IN TEXAS, 1845-1856.

[1] --Vide my paper on "Land Grants to Railroads in Texas," Appendix D, p. 92.

[2] --Act of February 11, 1850, "Laws of Texas," Vol. 3, p. 632.

[3] --The action of the company in beginning at Houston was ratified by the Act of February 7, 1853, Ibid, Vol. 3, p. 1390.

[4] --Donaldson, Loc. cit. pp. 121, 122.

[5] --Vide my paper on "Land Grants to Railroads in Texas," pp. 49, 50.

[6] --Ibid, Appendix D., p. 32.

[7] --"The subject of a railroad to the Pacific Ocean is one that is now engrossing the attention of every part of our widely spread LTnion. To none is its location fraught with more important consequences than to our State, and I therefore again briefly but most earnestly recommend it to your serious consideration" —Message to the Fifth Legislature in the Journal of the House of Representatives, p. 15, et. seq.

[8] --Act of December 21, 1853, "Laws of Texas," Vol. 4, p. 7.

[9] --Governor Pease's Veto Message of the Act to amend the Charter of the Texas Western Railroad, July 7, 1856, In the Journal of the Senate of the State of Texas, Sixth Legislature, Adjourned Session, Austin, 1856, pp. 15-18.

[10] --Governor Pease's Message to the Sixth Legislature, Ibid, p. 8.

[11] --Letter of Governor Pease to the Senate Committee on Internal Improvements, Senate Journal, Sixth Legislature, Adjourned Session, Austin, 1856, p. 99.

[12] --Debates of the Sixth Legislature in the State Gazette Appendix, Vol. 4, pp. 88-118.

[13] --Message of Governor Pease to the Sixth Legislature, 1855, Senate Journal, p. 8, et seq. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

[top] |

|

| |

|

|

| |

NOTES FOR SECTION IV., STATE AID TO RAILROADS.

[1] --Cyclopedia of Political Science, Political Economy and the Political History of the United States, edited by John J. Lalor, Vol. 3, p. 515.

[2] --Vide my paper on "Land Grants to Railroads in Texas."

[3] --Resolution of Congress, approved March, 1845, "Laws of Texas," Vol. 2, p. 1229.

[4] --Report of the Commissioner of the General Land Office of the State of Texas upon the Findings of the Special Commission appointed under the Act of March 2, 1899, November 7, 1899, p. 4.

[5] --Act of February 10, 1852, "Laws of Texas," Vol. 3, p. 1145.

[6] --These were: the Texas Central, the Texas & Louisiana, the New Orleans, Texas & Pacific, the Texas Western, the Vicksburg & El Paso, the Brownsville & Rio Grande, the Galveston, Houston & Henderson, the Indianola & Victoria Plank, the Marshall Railroad, the Memphis, El Paso & Pacific, the Virginia Point & Austin, the Columbia, Wharton & Austin, the Sabine & Sulphur Springs, and the Chambers terraqueous Transportation.

[7] --Vide my paper on "Land Grants to Railroads in Texas," pp. 25-28.

[8] --Twelfth Decennial Census of the United States.

[9] --"If we pursue this course our railroad charters will cease to be offered for sale by individuals who have obtained them for the purposes of speculation. Those who wish to construct railroads will obtain charters without paying a premium to the persons who have induced the Legislature to pass them, and we shall have no more companies organized without capital to impose upon the credulous and unwary, and stand in the way of those who have the disposition and means to construct railroads."—Message of Governor Pease to the Sixth Legislature, Senate Journal, 1855, p. 8.

[10] Report of the Comptroller of Public Accounts for 1858. The following were the elements of this estimate:

Land -- $73,677,316

Town Lots -- 12,861,990

Negroes -- 71,912,496

Horses -- 11,583,247

Cattle -- 13,259,537

Capital -- 2,745,493

Miscellaneous -- 6,347,298

Total -- $192,387,377

[11] -- Texas Almanac for 1859, p. 220.

[top]

[12] -- The condition of affairs is thus admirably summarized by the House Committee on Internal Improvements:

"It may be proper to advert to some of the causes that have hitherto delayed and prevented the construction of railroads in the State notwithstanding the liberal bonus of land. Some years back when most of our charters were granted, eight sections were pledged to the mile constructed. At that time the railroads in the Atlantic States had not approached the banks of the Mississippi or of the Gulf. A railroad to the Pacific Ocean was not regarded as a practicable undertaking, nor had it been ascertained that this work must pass through Texas. Our population was much more sparse and our products much less than now. Our railroads could not connect themselves with any of the great lines of travel connecting with the east web of railroads in the States east of the Mississippi, and it was evident that the freight and passenger travel within our own borders would not be sufficiently profitable to justify the investments of capital. Our lands were believed to be remote from navigable rivers and the low price of land certificates depreciated their value. A grant of sixteen sections per mile by the United States to railroads in the Northwestern States leading from Chicago, St. Louis, and other large market towns and, connecting with the railroads of the Atlantic cities, drew off from our State the attention of all persons disposed to engage in such undertakings; therefore, the hopes of our chartered companies, and citizens generally, were disappointed. At the last session of the Legislature the bonus was increased to sixteen sections, but unfortunately about that period the western nations of Europe engaged in a most expensive war so pressing that no new railroad enterprise could command the attention of capitalists either in the United States, London or Paris, so that another failure has attended the liberal offers of Texas." Journal of the Sixth Legislature of the House of Representatives, Part II, pp. 401-412.

[13] -- Poor's "Manual of Railroads for 1900," loc. cit., p. xxv.

[14] -- Encyclopedic Dictionary of American History, Vol. 1, p. 241.

[15] -- Cyclopedia of Political* Science, Political Economy and the Political History of the United States, Vol. III, p. 49.

[16] -- Report of the Committee on Internal Improvements, Sixth Legislature, 1856, House Journal, Part II, pp. 401-412.

[17] -- Debates of the Sixth Legislature, Regular Session, Vol. 1, p. 156.

[top]

[18] -- Message to the Sixth Legislature, Senate Journal, 1855, p. 8, et seq. The situation and prospects, are thus described: "We have chartered thirty-seven railroad companies and have held out greater inducements for their construction than were ever offered before by any government. It is now nearly four years since a bonus of eight sections of land was offered for each mile of road constructed, and nearly two years since the bonus was increased to sixteen sections a mile for each twenty-five miles. The result of these efforts has been that we have one road of about thirty miles in operation from Harrisburg on Buffalo Bayou to the neighborhood of Richmond on the Brazos River, and two others, the Galveston & Red River Railway, and the Galveston, Houston & Henderson Railroad in the course of construction, with a reasonable prospect, as I am informed, of completing twenty-five miles each by the 30th of January next in time to avail themselves of the bonus of sixteen sections. So far as I have been able to learn, no other company is doing any work under its charter * * *.

"The Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado Railroad Company will undoubtedly complete its road as far as Richmond during the present year. The Galveston & Red River Railroad Company, and the Galveston, Houston & Henderson Railroad Company expect to complete twenty-five miles of their respective roads by the 30th of January, 1856, so as to secure the bonuses of sixteen sections to the mile.

"These companies will then have to continue their roads at the rate of twenty-five miles a year or lose the benefit of the bonus of sixteen sections. If they fail to do this, the Harrisburg Company and the Henderson Company may still have the benefit of the bonus of eight sections, but the latter to secure even this, will have to construct an additional fifteen miles on or before the 1st of March, 1857, to save its charter.

[top]

"The Houston Company has already lost the benefit of the bonus of eight sections by failing to complete ten miles of its road within the time prescribed by its charter. It is possible that some of the other companies may be able to avail themselves of the sixteen section bonus, as only those which terminate on the Gulf coast, the Bays thereof, or on Buffalo Bayou, are subject to the provisions which require the construction of twenty-five miles on or before the 30th of January, 1856, though it is believed that few, if any of them, will ever build road enough to save their charters. It is not generally supposed that either of the three companies named will be able to construct their roads at the rate of twenty-five miles a year after the 30th of January next, so as to secure the sixteen section bonus unless they are assisted by a liberal loan of money from the State. We cannot therefore expect that much progress will be made for many years to come in the construction of railroads in this State by private corporations beyond the completion of these tracks already graded, unless such a loan shall be authorized, or that provision of the act which requires these companies to construct twenty-five miles a year is repealed, for it is generally conceded that they will not at present yield a sufficient profit to induce individuals to invest capital in them without the advantage derived from the land bonus."

[19] -- Message to the Fifth Legislature, Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Texas, Austin, 1853, Part II, pp. 22-25.

[20] -- Report of the Committee on Internal Improvements, House Journal, Fifth Legislature, p. 186.

[top]

[21] -- The details of this plan will be gleaned from the following excerpts from Governor Pease's Message:

"The present is a favorable time to revise our legislation in regard to railroads generally. * * *

"What our citizens need is a general system of internal improvements by railroad, river improvements and canals that will extend its benefits to every section of the State as nearly as practicable, and give them a cheap transportation of their products to market. This I believe can be obtained within the next 'fifteen years by a judicious use of our public domain, aided by a moderate internal improvement tax, which will never be onerous to our citizens, and for which will be repaid ten fold in the increased value that such a system will give to their property, and the reduced rate at which they will be furnished transportation of their productions and their supplies.

"Our unappropriated public domain is estimated at about 100,000,000 acres. Suppose that one-half of it was valueless or unsuitable for cultivation, which is a large estimate, this will leave us 50,000,000 acres, which at seventy-five cents an acre is worth $37,500,000. This every one must admit is a small estimate of its value, and under a judicious system of sales, to be effected gradually as the wealth and population of the State is increased by the proposed improvements, it would undoubtedly sell for twice or three times that amount within fifteen years. Let us suppose that it would cost six cents an acre, which is a large price, for the gradual survey of these lands as it might be deemed advisable to bring them into market, the cost of surveying the whole hundred millions would be $6,000,000. This would leave $31,500,000 as their net proceeds to be applied to works of internal improvement. As this amount could be realized from them only by gradual sales through a course of years, in order to commence the system immediately, it would be necessary to anticipate their proceeds by the use of the credit of the State, to sustain which an internal improvement tax of fifteen cents on each $100 of the taxable property of the State would be required. Such a tax on the assessment for the year 1857, which is as early as the system could be commenced, would produce * * * $268,000 this would pay an interest of six per cent, on four and one-quarter million dollars. The same tax, allowing the increase in the value of our taxable property to be one-fourth less each year than it has been since the year 1846 (and it would without doubt be much greater), would produce in 1860 the sum of $337,000, which would pay an interest of six per cent. on six and one-quarter million dollars. This will enable us to use the credit of the State to the amount six and one-quarter million dollars before the close of the year 1860, without taking into account the annual earnings of the public works as they progress, which would be at least three per cent, on their cost, equal to one-half of the interest we would be paying on the debt. By that time we would be in receipt of a considerable amount each year from the sale of the public domain, increased in value by the improvements already made, and our works could proceed much more rapidly to completion. In this way we might expend from twenty-five to thirty million dollars upon a general system of internal improvements within the next eighteen years and at the end of that time the whole will have been paid by the proceeds of the sale of our public domain and the internal improvement tax. The State would be the owner of the works constructed and could reduce the price for transportation and travel to such rate as would keep them in repair and pay the expense of operating them, or to such rates, as in addition to the cost of keeping them in repair and operating them, would produce an annual income of three per cent. upon the cost. This income amounting to over $750,000 might be applied to the expenses of the government, or to extend the system until every neighborhood in the State would be furnished with ample railroad facilities. All this may be accomplished and the wealth of our citizens increased hundreds of millions, simply by a prudent use of our public domain and an annual tax of fifteen cents on each $100 of the taxable property of the State for the next fifteen years. The system of works should consist of railroads, improvements upon our navigable rivers and canals connecting the different bays and streams along our coast.

[top]

"Sixteen hundred miles of railroad can be so located as to accommodate every section of the State that is now inhabited, and so that no neighborhood (except the northwest corner of the State) that is not within a convenient distance of a navagible course or a canal shall be more than twenty-five miles from a railway.

"The average cost of building and equipping railroads in this State will not exceed $10,000 a mile if paid for with money when the work is done; at this rate sixteen hundred miles would cost $25,600,000. This amount deducted from thirty-one and a half million, the estimated sum to be derived from our public domain in the next fifteen years would leave $5,900,000, which could be applied to the improvement of our navigable rivers, cutting canals to connect all the bays and water courses along our coast from the Sabine and Rio Grande, and to any other object of public utility.

"This system to be successful must be made the permanent policy of the State and incorporated into our Constitution so as to be placed beyond reach of change by Legislation.

"The routes over which railroads are to be constructed, the rivers whose navigation is to be improved, and the canals which are to be cut, must be specified —the lands must be set apart as an internal improvement fund—the time and manner of their survey and sale must be fixed—the internal improvement tax must be levied—provision must be made that the credit of the State shall never be used to an amount beyond what the internal improvement tax and the net earnings of the public works will pay the interest of—and that the works specified shall all be carried on simultaneously until their final completion— all this must be done by constitutional provision—otherwise it is possible that future Legislatures may undertake other works before those designated shall have been completed, or may become impatient with the progress of the works and endeavor to hasten their completion by an increase of taxation, so as to make it oppressive, or by the use of the State credit beyond the means provided for sustaining it, and thereby defeat the whole system.

[top]

"Under this system, the improvements will progress towards completion simultaneously with the increase of population and the wealth of the State. Each mile of improvement will increase the value of the public lands and of individual property, and the ability of the State to prosecute the system will increase in the same ratio. * * * No system of internal improvements should be undertaken requiring an expenditure of money by the State, which would have to be supplied by taxation, until it has first been submitted to and received the sanction of the people. * * *.

"Should these views be acceptable to you, I shall interpose no obstacles to such constitutional measures as you may adopt to aid in the construction of railroads and in the improvement of our navigable rivers, if they shall seem likely to effect those objects * * *." Journal of the Senate of the State of Texas, Sixth Legislature, Austin, 1855, pp. 18-31.

[22] -- Robert's "The Political, Legislative and Judicial History of Texas for its Fifty Years of Statehood, 1845-1895," in Scarff's "A Comprehensive History of Texas," Vol. 2, pp. 21-29.

[23] -- "Laws of Texas," Vol. 3, p. 1461.

[24] -- Senate Journal, Fourth Legislature, Austin, 1851, pp. 31-33.

[25] -- House Journal, Fifth Legislature, Austin, 1853, Part II, pp. 22-25.

[26] -- "Laws of Texas," Vol. 4, p. 449. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

[top] |

|

| |

|

|

| |

NOTES FOR SECTION V., RAILROAD REGULATION.

[1]--Debates of the Sixth Legislature, Regular Session, Vol. 1, p. 177.

[2]--Report of the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado Railroad to the Comptroller for 1860.

[3]--Debates of the Sixth Legislature, Regular Session, Vol. 1, p. 178.

[4]--Ibid, Vol. 1, p. 178.

[5]--Journal of the House of Representatives, Fourth Legislature, Austin, 1853, p. 15 et seq.

[6]--Journal of the House of Representatives, Fifth Legislature, Austin, 1853, Part II, pp. 22-25.

[7]--Acts of February 13, 1854 and February 4, 1864, "Laws of Texas," Vol. 4, p. 142 and 70.

[8]--"No new charters should be granted over a route where a road is already being constructed, or near such route as materially to impair its value.

"Every railroad company should be required to hold all meetings for the election of its officers within the State, and have a majority of its directors resident citizens thereof, and also to keep its principal office for the management of its affairs within the State. * * *

"I am unwilling that any new charters shall be granted to individuals for their own benefit. If new charters are necessary, let such routes be selected as the wants and business of the country require, designate their points of commencement and termination, and grant charters to commissioners who shall be required to open books for the subscription of stock after giving public notice. No subscription should be received unless five per cent, thereof is paid at the time of subscribing, and whenever the percentage on the capital stock subscribed shall amount to $100; let the commissioners be authorized to call a meeting of the subscribers and hold an election for officers, after which the subscribers should become a corporation with all such powers as are set forth in the charter. The commissioners should have no right under the charter except as trustees for the benefit of the subscribers."—Journal of the Senate, Sixth Legislature, Austin, 1855, p. 18 et seq.

[9]--Debates of the Sixth Legislature, Regular Session, Vol. 1, pp. 176-178.

[10]--Apt of July 24, 1856, "Laws of Texas," Vol. 4, p. 569.

[11]--Acts, of January 23, 1856, and February 4, 1856, Ibid, Vol. 4, p. 326, 328, 378.

[12]--Act of August 16, 1856, Ibid, Vol. 4, p. 622.

[13]--Act of January 24, 1856, Ibid, Vol. 4, p. 336.

[14]--Senate Journal, Sixth Legislature, Austin, 1856, pp. 11, 12.

[15]--Vide Journal of the House of Representatives, Tenth Legislature, Austin, 1857, pp. 38-41.

[16]--Act of December 17, 1857, "Laws of Texas," Vol. 4, p. 987. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

[top] |

|

| |

|

|

| |

NOTES FOR SECTION VI., RAILROAD PROGRESS, 1856-1860.

[1]--Act of January 22, 1858. "Laws of Texas," Vol. 4, p. 529. This act amended the act of 1J56 so as to allow companies to receive loans on the five miles of road after the completion of the first twenty-five miles.

[2]--Published statements to the stockholders of the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado Railroad on the condition of the company for the years 1858 and 1860. The entire equipment of the company consisted on the 1st of April, 1860, of six locomotives, three first-class passenger cars, two second-class passenger cars, mail and baggage cars, sixty-one platform and twenty box freight cars, and ten hand and rubble cars.

[3] See table below:

[top]

[4]Act of September 1, 1856, "Laws of Texas," Vol. 4, p. 806.

[5]Report of the Houston & Texas Central Railway in the Texas Almanac for 1861, p. 234.

[6]Fourth Annual Report of the President and Directors of the Houston & Texas Central Railway Company to the Stockholders, 1857, p. 10.

[7] The account of the company stood on June 1, 1860, as follows:

Stock subscribed to June 1, 1860:

Stock issued and fully paid --- $ 458,200.00

Stock paid, but not issued --- 320,475.00

Due for stock in bills receivable --- 264,124.00

Total --- $1,042,800.00

Construction account, buildings at Courtney and Navasota stations, platforms since last --- $19,514.00

Right of way --- 187.51

Land from the State --- 1,608.00

Three locomotives --- 30,000.00

Cars and material for cars --- 14,815.00

Amount of bonds to the State of Texas --- 450,000.00

Amount of bonds, second mortgage --- 125,000.00